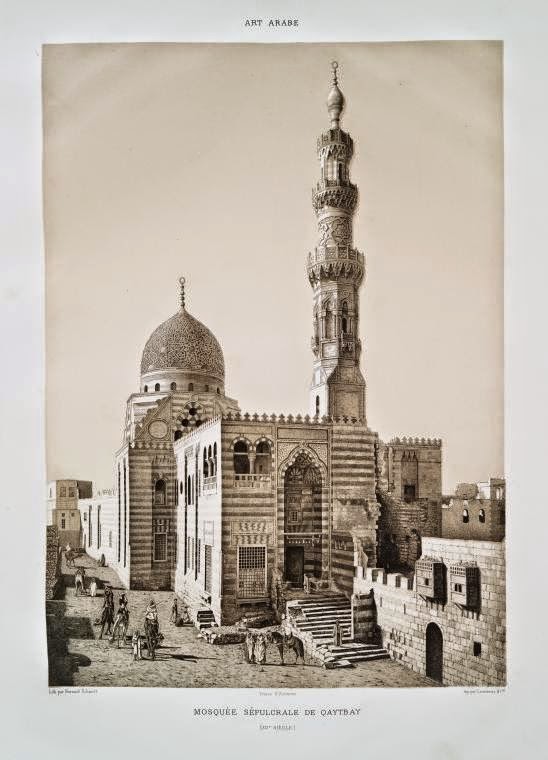

View of Funerary Complex of Qaytbay, Northern Cemetery, Cairo

By Leon von Ossko (1859-1906)

1901

The Phillips Museum of Art at Franklin and Marshall College is a treasure-trove of artifacts that we are in the process of cataloging.

Leon von Ossko (1859-1906) was a Hungarian nobleman. The baronial title was bestowed on the von Osskos, interestingly enough, for fighting the Ottomans in the Ottoman-Habsburg Wars. Although Hungarian, Leon was raised in Germany and attended university at Heidelberg. After his graduation, he traveled through the United States for two years with a cadre of European aristocrats, exploring the Wild West. Between Denver and the Pacific Ocean the group encountered conflicts with native American tribes and von Ossko was wounded. During that American journey, von Ossko met Ella Louisa Breneman, the daughter of Christian Herr Breneman, a prominent citizen of Lancaster county. Their courtship lasted for two years across two continents. They were married in Florence in 1884.

Von Ossko became an accomplished artist studying in Florence and at the Academy Julian in Paris. After his marriage to Ella, he moved to Lancaster. Little is known of his artistic production. In a biographical note (Breneman 1912), we read that his oils and water colors were exhibited widely across New York, Philadelphia, Washington, Baltimore and Cincinnati. The drawing found at the Phillips Museum has an orientalist subject, the Mamluk funerary complex of Qaytay, in the Northern Cemetery in Cairo (15th century). I thank Emily Neumeier and Christy Gruber for making the precise identification. I also thank Benjamin Anderson for identifying a particular fascination of this monument by German viewers. In his blog post "A Piece of the Orient on the Elbe,” Stambouline (July 17, 2015), Anderson offers a similar view published in Émile Prisse d’Avennes, L’art arabe (1869-77), shown left.

It is so intriguing to think of Lancaster, Pennsylvania, as an epicenter of German Romantic Orientalism through some newcomers, like von Ossko. The drawing is dated 1901 at the bottom right. As early as the 17th century, Germanic colonists in Lancaster County had direct exposure to the Islamic world through the Ottoman Empire, which reached Vienna. A current exhibition on Pennsylvania German Fraktur at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, for example, includes a drawing depicting Ottomans drawn in Pennsylvania. Some of the iconographic motifs in Pennsylvania German art (tulips, etc.) have Ottoman origins. But this larger question of German orientalism transplanted in Pennsylvania is a fascinating unstudied topic.

It is interesting to note that Lancaster's current City Hall (left) makes references to Islamic architecture (the Alhambra). Originally designed as a Post Office by Philadelphia architect James Windrim (1891), Lancaster's City Hall would have gone up just ten years before Von Ossko had done his drawing [On Lancaster City Hall, see here, p. 8]

Unfortunately, there is very little historical coverage on Lancaster's orientalist painter. We do not even know how Franklin & Marshall College ended up with this drawing. The Brenemans were related to Caroline Peart, a little known but important American Impressionist. Our college has received Peart's archive and von Ossko's drawing might have come as part of that package. On the subject of Caroline Peart, make sure to see her painting currently hanging at the Nissley Gallery of the Museum and look forward to a massive retrospective curated by our Kate Snider.

Unfortunately, there is very little historical coverage on Lancaster's orientalist painter. We do not even know how Franklin & Marshall College ended up with this drawing. The Brenemans were related to Caroline Peart, a little known but important American Impressionist. Our college has received Peart's archive and von Ossko's drawing might have come as part of that package. On the subject of Caroline Peart, make sure to see her painting currently hanging at the Nissley Gallery of the Museum and look forward to a massive retrospective curated by our Kate Snider.

In trying to put together the urban topography of Lancaster and its prominent citizens, I did some research on the house where this drawing might have originally hung, the house of Leon von Ossko and his wife Ella Louisa Breneman. It is a beautiful Greek Revival townhouse built in 1852, located at 47 North Lime Street (SE corner of Lime and Orange).

The house's most outstanding feature is its marble porch with classically correct decoration that stands out among the Palladian wooden porches common to Lancaster. The house has its original iron work.

Von Ossko died in 1906 in Saint Augustine, Florida, where he had moved for health reasons. He was survived by two sisters that lived in Florence. One was married to a Count. I have not done any research on Anna Louisa Breneman and the Breneman family. The house seems to have been sold in 1937. In 1987, Tabor Community Services bought the house and converted it into Beth Shalom, or "House of Piece," an interim housing facility for women in need.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- Breneman, Harry. 1912. “Papers Read before the Lancaster County Historical Society. Friday, Novermber 1, 1912,” Historical Papers and Addressed of the Lancaster County Historical Society 16, no. 9, pp. 273-275.

- Jacobsen, Anita. 2002. Jacobsen’s Biographical Index of American Artists, vol. 1, book 4, Carrollton, Tx., p. 3339.

- Pennsylvania Society. 1907. “Miscellaneous,” Yearbook of the Pennsylvania Society, p. 227. [New York]

- S. M. S. 1906-1907. “Obituary. Leon von Ossko,” Historical Papers and Addressed of the Lancaster County Historical Society 11, p. 36. [Lancaster]

.jpg)