Saturday, January 31, 2009

Follow the White Marble Road to Halandri

"The Ancient Road of Marble," was announced in yesterday's Eleutherotypia newspaper. The excavation was supervised by Giouli Papageorgiou of the 2nd Ephoria of Prehistoric and Classical Antiquities. The ancient road is 3.30 m wide and it contains the expected wheel ruts. What is wonderful for post-classical archaeologists (like myself) is the presence of a Frankish coin indicating the road's continued use into the 13th and 14th c. According to the secondary literature on this issue, all marble quarries stopped functioning after antiquity. Penteli's quarry was opened up again in the 19th century for the rebuilding of neoclassical Athens. Research on medieval quarries is in its infancy. Frederick Cooper and Sarah Franck (University of Minnesota) have been studying the issue with G.I.S., and Demetris Athanasoulis (Ephor of Byzantine Antiquities in Corinth) has been tracking limestone quarries connected to the foundation of Glarentza and Kastro Chlemoutsi. A coherent picture is emerging for the Frangokratia in the Peloponnese with new limestone quarries servicing the need for ashlar detailing (quoins, rib vaults, sculpturalal relief, gargoyles, etc.)

What is personally exciting about the new stretch of the marble road is its location in the ravine of Halandri near my friend Anna Androulaki's house. I've spent endless summer hours on Anna's balcony between field projects. All of Athens seemed to have vacated and we splurged on DVD marathons of the Sopranos, Haagen Dazs, peinirli, and Penne alla Vodka. Anna's son, Patroklos, is my godson. When he was eight years old, I decided to take him on his first "archaeologcial expedition." Since I would go to Greece and then disappear up in the mountains, Patroklos had created an inflated idea of how "cool" my job was. So, I decided to give him a true taste. I got him a compass and a notebook and we headed up the mountain to the quarries of Penteli. Actually, Anna drove us up there, but we walked back on our own (for hours). It was one of my fondest days in Athens: me and my godson crawling through quarry caves and Byzantine churches, looking down upon Athens, all alone with no other soul in sight. The walk back was interesting, too, since Patroklos insisted on wearing his unlaced Run DMC sneakers for the occasion. Once we reached civilization, we took a bus to downtown Athens. It became clear to me at that point that Patroklos had never taken an Athens city bus. The adventure was topped by a special bookstore visit to buy the latest volume of my favorite children's literature, Lemony Snicket's A Series of Unfortunate Events, just translated into Greek.

Now, we don't have to take that journey anymore. We can simply walk to 133 Penteli Street and watch the marble road. But things have changed. My friend Anna and the kids have immigrated to Germany; Anna, an IB teacher, got a fantastic job at the Salem International College in Uberlingen. So, my godson became an immigrant at the age of fourteen, almost as old as I was when my family immigrated to the U.S. I feel an additional bond with Patroklos; such a transition is a mixed bag full of growth and excitement, on the one hand, but sadness and estrangement, on the other hand. I regret not being there for some sympathetic support. For Anna, Patroklos, and his sister Dynameni, the return to Halandri is the return from the Xenitia on the sporadic holiday. For me, Anna's house in Halandri fulfilled the need of an immigrant's return home. Paradoxically, the same house is now serving this very role for Anna and the kids. Circuitously, it emerges at the end of a different yellow-brick road. And my wife tells me that there is another circuitous path: Daniel Handler (aka. Lemony Snicket) is Wesleyan alumni.

Finally, I should mention that Patroklos is blooming into a successful recording artist, a proud representative of a small but booming hip-hop scene in Greece. So this last Christmas holiday, when her returned to Halandri from Germany, he spent his time at "home" in the recording studio, mixing the tracks of The Fat Free Yogurts (Άπαχα Γιαούρτια). Now I'm really glad he didn't compromise his unlaced shoes for the mountain of Penteli.

Friday, January 30, 2009

Tanagras and Kourouniotis

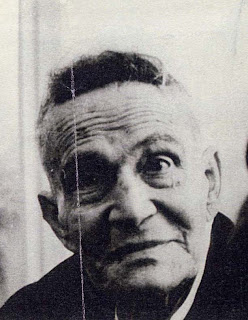

In my postings on Angelos Tanagras and archaeology, I contemplated certain lines of inquiry. Since then, I've found one more piece of evidence. Tanagras was friends with Alexander Philadelpheus, a very important Greek archaeologist. Reading through the list of case-studies in Psychological Elements in Parapsychological Traditions (New York, 1967), I was thrilled to find an entry by another very important Greek archaeologist, Konstantinos Kourouniotis, Director of the Archaeological Service (left, picture from Eleusina). In 1929, Kourouniotis submitted a report on paranormal activities to Tanagras' scientific journal, Psychic Researches. This suggests that Kourouniotis was not only a follower of Tanagras' theories but perhaps also a friend. His report was both public and signed. I quote the whole passage below, involving an incident of bee the exorcism. It does not involve the practice of archaeology per se, but it took place during Kourouniotis' fieldwork in Asia Minor. This is the period when Kourouniotis conducted excavations in Ephesus (the church of Saint John), an interesting chapter in Greek archaeology between the 1919 Treaty of Versailles (which granted Greece control of Asia Minor) and the 1922 "Great Catastrophe" (which ousted the Greeks from Asia Minor). For the archaoelogical geopolitics of that period, see, Jack L. Davis, "A Foreign School of Archaeology and the Politics of Archaeological Practice: Anatolia, 1922," Journal of Mediterranean Archaeology 16.2 (2003), pp. 147-173.

In my postings on Angelos Tanagras and archaeology, I contemplated certain lines of inquiry. Since then, I've found one more piece of evidence. Tanagras was friends with Alexander Philadelpheus, a very important Greek archaeologist. Reading through the list of case-studies in Psychological Elements in Parapsychological Traditions (New York, 1967), I was thrilled to find an entry by another very important Greek archaeologist, Konstantinos Kourouniotis, Director of the Archaeological Service (left, picture from Eleusina). In 1929, Kourouniotis submitted a report on paranormal activities to Tanagras' scientific journal, Psychic Researches. This suggests that Kourouniotis was not only a follower of Tanagras' theories but perhaps also a friend. His report was both public and signed. I quote the whole passage below, involving an incident of bee the exorcism. It does not involve the practice of archaeology per se, but it took place during Kourouniotis' fieldwork in Asia Minor. This is the period when Kourouniotis conducted excavations in Ephesus (the church of Saint John), an interesting chapter in Greek archaeology between the 1919 Treaty of Versailles (which granted Greece control of Asia Minor) and the 1922 "Great Catastrophe" (which ousted the Greeks from Asia Minor). For the archaoelogical geopolitics of that period, see, Jack L. Davis, "A Foreign School of Archaeology and the Politics of Archaeological Practice: Anatolia, 1922," Journal of Mediterranean Archaeology 16.2 (2003), pp. 147-173.Tanagras recounts Kourouniotis' story in the chapter, "Psychobolic Influence on Animals,"Psychological Elements in Parapsychological Traditions, p. 65.

"CASE 62. Professor C. Kourouniotis, the ephor of antiquities and head of the archaeological section at the Ministry of Education, has reported the following case, which was published in the Psychikai Ereunai, January, 1929: In 1920, during the Greek occupation of Asia Minor, Professor Kourouniotis was at Eskihesir, for the purpose of exmining the local antiquities. For his accomodation, an empty house had been requisitioned, and in the door of this house, at a height of six fee, a swarm of bees had built their nest. Every effort was made to dislogde the nest, without success, and, as the maidservant was very disturbed by the proximity of the bees, they were advised to call in a hodja (Turkishy priest) who had the ability of 'exorcising' and would therefore be able to solve the problem. Mr. Kourouniotis acceded to the appeals of the maid and called the hodja, who came in the evening and stayed for some time in order to pray. The bees were not seen again and no dead bees were found, as would have been the case if fumigation or a poison had been used. (signed) Professor C. Kourouniotis."

It is important to stress that Tanagras sought scientific principles behind these occurances, and there is no reason to think that Kourouniotis was any less scientific in his approach. The Tanagras Theory belongs to a fascinating moment in the history of science where Einstein's relativity, Curie's radiology and Freud's psychoanalysis coalesce into one discipline. According to Tanagras, animate beings (both animals and humans) emit psychic rays, similar to X-rays, that directly affect the physical world. His discipline of Parapsychology sought to substantiate, to experiment on, and to explain the processes of psychic projection. It was not, therefore, an enterprise of the occult but a respected scientific endeavor with many followers of high social standing in Greek society. Tanagras traveled throughout Greece to collect evidence and published authoritative eye-witness reports by other trustworthy sources

Thursday, January 29, 2009

Teaching Thursday: History of Domestic Architecture

This week I started teaching my first class at Wesleyan University, in the Graduate Liberal Studies Program (GLSP). For years now, I had been thinking about a class that introduces the history of houses from antiquity to the present concluding, of course, with the domus of the sub-mortgage crisis. Beyond a chronological survey, I envisioned an introduction in the methodologies and theories of house architecture. Luckily, others were intrigued and History of Domestic Architecture (ARTS 637) quickly filled its enrollment. In our first class, I was thrilled to meet the GLSP student body, adult students, mostly high school teachers. Connecticut's secondary education system rewards teachers who receive a Master's in the Humanities. The class includes other professionals, such as curators at the Yale University Art Gallery, Wesleyan employees, contractors and real estate specialists. I don't think there are too many schools that offer histories of domestic architecture. If anyone would like to replicate or build on this class, I would be more than happy to share my electronic bulk pack (PDF files). The syllabus follows.

Kostis Kourelis

History of Domestic Architecture

Class: Monday, 6:30-9:00 pm, Fisk Hall 115

Email: kkourelis@gmail.com

Tel: 860-685-0150

COURSE DESCRIPTION

Domestic form has captured the cultural imagination throughout history. From Adam's house in paradise to Mohammed's house in

Sources to be studied include house architecture, primary and secondary scholarship related to the history of domestic architecture from antiquity to the present. The majority of the readings will be available as PDF documents on the course website. Two required textbooks are available at the bookstore.

Wright, Gwendolyn. 1981. Building the Dream: A Social History of Housing in

CLASS REQUIREMENTS

Grades will be based on homework assignments (40%), class assignments and participation (40%) and a short final research paper (20%).

SCHEDULE

1. The Primitive Hut

Humanity’s transition from a state of nature into a state of civilization has been narrated through the construction of the first dwelling. The origins of architecture have been theorized along with the origins of language. By investigating the “primitive hut” across cultures and theorists, we will set the stage for the discursive depths of a simple hut. We will look at both ethnographic huts, and also at the foundations of architectural theory in Vitruvius (1st c.), Marc-Antoine Laugier (18th c.), Gottfried Semper (19th c.) and others.

Vitruvius. 1st c. BCE. “The Origin of the Dwelling House,” from The Ten Books of Architecture (II.1), trans. Morris Hicky Morgan, New York (1914), pp. 38-41.

Laugier, Marc-Antoine. 1753. “General Principles of Architecture,” in An Essay on Architecture, trans. Wolfgang and Anni Herrmann, Los Angeles (1977), pp. 11-13.

Semper, Gottfried. 1851. “The Four Elements of Architecture: A Contribution to the Comparative Study of Architecture,” in The Four Elements of Architecture and Other Writings, trans. Harry Francis Mallgrave and Wolfgang Herrmann, Cambridge (1989), pp. 102-110.

Le Corbusier. 1923. “Regulating Lines,” in Toward a New Architecture, trans. Frederick Etchells,

Oliver, Paul. 2003. “True to Type” ch. 3, Dwellings: The Vernacular House World Wide,

2. Oikos, Domus, Villa

We will start our historical survey by investigating the ancient Greek house from an archaeological point of view. The Greek oikos and the Latin domus gave birth to theoretical considerations from oikonomia (economy), equality, citizenship, democracy and the creation of the civilized polis. The Roman villa, our second building type, will reveal the relationship between the arts and domestic architecture. We will move away from the city and consider the house in a rural context as a unit of agricultural production and ecology.

Nevett, Lisa. 2007. “Housing and Households: The Greek World,” in Classical Archaeology, ed. Susan E. Alcock and Robin Osborne,

Bergmann, Bettina. 2007. “Housing and Households: The Roman World,” in Classical Archaeology, ed. Susan E. Alcock and Robin Osborne,

3. From Castle to Palazzo

Chronologically, we move away from antiquity into the Middle Ages and the Renaissance. Both periods have left us with two unique domestic forms. We will study the sociological dimensions of castles and palazzos, and, more importantly, how they contributed to the self construction of their elite occupants.

Stalley, Roger. 1999. “Secular Architecture in the Age of Feudalism,” ch. 4, Early Medieval Architecture,

Ackerman, James. 1997. “Palladio’s Villas and Their Predecessors,” ch 4, The Villa: Form and Ideology of Country Houses,

4. Houses of Enlightenment

During the 18th century, the house became a site for enlightenment, sensual discovery, pedagogy, history and taste. We will read a short treatise, The Little House: An Architectural Seduction, by Jean-Françoise de Bastide (1758) and also consider the elements of culture in contemporary houses like Thomas Jefferson’s

De Bastide, Jean-Françoise. 1758 (1996). The Little House: An Architectural Seduction, trans. Rodolphe el-Khoury,

Lewis, Michael J. 2002. “Romanticism,” ch. 2, The Gothic Revival,

5. Structures of American Life

When the first British settlers arrived in

Deetz, James. “I Would Have the Howse Strong in Timber,” ch. 5, In Small Things Forgotten: An Archaeology of Early American Life,

Upton, Dell. 1998. “An American Icon,” ch. 1, Architecture in the

6. The Cult of Domesticity

Moving chronologically from the 18th and early-19th centuries into the late 19th century, we discover a radical shift in the conceptions of the house. The cult of domesticity and the functional specialization of the family are two new elements that continue to dominate our own concepts of home. We will investigate the Victorian cottages in the garden suburbs and the parallel development of domestic reform and welfare.

Wright, Gwendolyn. 1981. “Victorian Suburbs and the Cult of Domesticity,” “The Progressive Housewife and the Bungalow,” in Building the Dream: A Social History of Housing in America, Cambridge, Mass., pp. 93-113, 158-176.

Beecher, Catharine A. and Harriet Beecher Stowe. 1869 (1975). “The

Downing, Andrew Jackson. 1850. “Designs for Villas or Country Houses,” in The Architecture of

7. The House Beautiful

An under-appreciated side of modern aesthetics is the cultivation of the house as a work of art. Stylistic eclecticism (Italianate, Carpenter Gothic, Queen Anne, Tudor, etc.), the Arts and Crafts movement, the House Beautiful movement, as well as growth of interior decoration as a field of feminine expression upstaged domestic life into the level of self-construction. The

Clark, Clifford Edward, Jr. 1986. “The House as Artistic Expression,” ch. 4, The American Family Home, 1800-1960,

Gere, Charlotte, with Leslie Hoskins. 2000. “The Art of Decoration,” The House Beautiful: Oscar Wilde and the Aesthetic Interior,

8. Being, Dwelling, Dreaming: A Theoretical Interlude

Before leaving the 19th century, we will take a chronological break and delve into deep theoretical waters. We will consider the modern house from the perspective of psychoanalysis, Marxism and phenomenology, reading house treatises by Sigmund Freud, Karl Marx and Martin Heidegger respectively. This will offer less insight into the architectural development of the house. Rather, it will remind us of the origin myths with which we started this class and let us appreciate the theoretical significance of the house in modern theory.

Freud, Sigmund. 1925. “The Uncanny,” in The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, ed. and trans. James Strachey, v. 17,

Marx, Karl. 1867. “The Fetishism of Commodities and the Secret Thereof,” from Capital: An Abridged Edition, ed. David McLellan,

Heidegger, Martin. 1954. “Building Dwelling Thinking,” in Poetry, Language, Thought, trans. Albert Hofstadter,

9. Machines for Living

Modernism envisioned a radical break with the traditional house. According to Le Corbusier, a house should a machine for living. We investigate the fundamental role that dwellings played in the revolution of modern architecture, dwelling in both the innovative and common elements of this new style.

Le Corbusier. 1923 (2007). Towards an Architecture, trans. John Goodman,

Curtis, William J. R. 1996. “The Image and Idea of Le Corbusier’s Villa Savoye at Poissy,” from Modern Architecture since 1900, 3rd ed.,

Rowe, Colin. 1976. “The Mathematics of an Ideal Villa,” in The Mathematics of the Ideal Villa and Other Essays,

10. Public Utopias

One of modernism’s most powerful dreams was the eradication of industrial society’s problems, namely the gulf between capital and labor, between the middle class and the proletariat. Modernists tackled society’s foundations by rethinking public housing. We will study the utopian projects of public housing in early 20th century Europe and

Wright, Gwendolyn. 1981. “Americanization and Ethnicity in Urban Tenements,” “Public Housing for the Worthy Poor,” Building the Dream: A Social History of Housing in America, Cambridge, Mass., pp. 114-134, 220-239.

Curtis, William J. R. 1996. “The Ideal Community: Alternatives to Industrial Living,” in from Modern Architecture since 1900, 3rd ed.,

11. Private Dreams

The development of the post-War suburb altered the way that most Americans live. This transformation was fundamentally domestic. The single-owned private home was part reality, part fiction. We will study the creation of the suburb and its relation to both the American dream and the abandonment of cities (white flight). We will conclude with the last episode of this movement, the exburbs and MacMansions, and the effects of this private dream in the urban (neighbor)hood. We will attempt to correlate the hip-hop “crib” with phenomena as diverse as the sub-mortgage crisis, globalization, the abandonment of Projects and the movement of New Urbanism.

Wright, Gwendolyn. 1981. “The New Suburban Expansion and the American Dream,” ch. 13, Building the Dream: A Social History of Housing in

Nelson, George and Henry Wright. 1945. Tomorrow’s House: A Complete Guide for the Home-Builder,

Friedman, Alice T. “People Who Live in Glass Houses: Edith Farnsworth, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, and Philip Johnson,” Women and the Making of the Modern House: A Social and Architectural History,

12. Missing Home

In this final class, we will ask a simple question: Is the quest for “home” a legitimate or a self-deluding project for our times? In order to answer this question we will look at an odd array of case studies: house-museums, fantasies of vernacular, and the return-to-nature. Global warming and ecological concerns have put the design of houses back into the forefront of identity politics. We leave with an open question framed between fantasy and reality.

Venturi, Robert, Denise Scott Brown and Steven Izenour. 1972. “Ugly and Ordinary Architecture, or the Decorated Shed,” part 2, Learning from Las Vegas, rev. ed., pp. 87-103.

Rybczynski, Witold. 1986. “Nostalgia,” from Home: A Short History of an Idea,

Colomina, Beatriz. 1998. “The Exhibitionist House,” in At the End of the Century. One Hundred Years of Architecture, ed. Russell Ferguson,

Wednesday, January 28, 2009

Tanagras and Archaeology

There is the metaphor of digging through the layers of memory to get through the psyche, the Jungian search for mythological archetypes, or simply the primitive fascination of physically connecting to your ancestors (father, mother) by digging up their graves--defiling them and celebrating them in the same action. Michael Shanks has related the archaeological sentiment with Julia Kristeva's notion of the Abject; in so many words, the archaeologist has a fundamental cultural need to get dirty, to play with his own shit in the sandpit.

But more specifically onto Tanagras, I'm brainstorming to find any specific connection that might contribute to Caraher's thesis. I don't have a clear answer but a few thoughts.

1. The name Tanagras reveals an archaeological sensibility. I do not know when Tanagras chose this literary pseudonym and, more importantly, why. As far as I know, the family originated from Paros, so there is no regional connection to Boeotia. Tanagra became a famous site when in the 1860s, some farmers ploughed through Hellenist tombs full of terracotta figurines. The naturalistic pose and the preserved pigments on the little statues appealed to the contemporary aesthetics. The figurines became a late-19th-c. celebrity, flooding the antiquities market (including a number of fakes) and becoming standards of beauty for contemporary artists. Tanagras may have identified with the mythological figure Tanagra, the Naiad nymph that gave name to the ancient city. Naiads were the deities of wells, springs and fountains and Tanagras may have identified with the mythology of flows. At any rate, I suspect that he chose the name Tanagras, specifically, because of its reputation (thanks to the figurines) throughout Europe.

2. Going through the memory banks of what relatives have told me about Tanagras, I cannot find any referencet to archaeology. Nevertheless, I was shocked a few years ago to discover a dedication to Tanagras by Alexander Philadelpheus in his 1924 Monuments of Athens (Μνημεία Αθηνών). Philadelpheus was Greece's best known archaeologist of the early 20th c., he was director of the Archaeological Museum and quite international. He and Tanagras must have been good friends.

3. Caraher's fundamental question is the relationship between subjectivity and objectivity in archaeological practice. I have only one story to offer on this front regarding Tanagras. According to my aunts, Tanagras had an apartment on Aristotelous Street, where he held seances attended by some elite members of Athenian society. His professional research, after all, was on the communication of spirits and paranormal psychic activities. Among the regular attendants were members of the Police Department, who sought clues for solving crimes. This might seem bizarre to us today, but we must remember that through the early 20th-c. somnubalism, spiritualism and theosophy were considered mainstream intellectual positions. Madame Blatavsky comes to mind, the founder of the Theosophical Society. What distinguishes Tanagras from other spiritualists is his commitment to documentation, scientific objectivity and material proof. Tanagras seems to have filmed at least one of his subjects; he exhibited the film in 1935, at the 5th International Congress of Phychic Research in Oslo. Fotini Pallikari, professor of Physics at the University of Athens has presented fascinating new research on this controversial film, see "The 1935 Oslo International Parapsychology Congress and the Telekinesis of Cleio," International Conference of the Society for Psychical Research, University of Winchester, August 2008. Bill Caraher will especially appreciate this filmic side of Tanagras, given his interest in documentaries and video (see PKAP).

This is all to say that there at least a spiritual connection between Tanagras and archaeology but perhaps more. It is hard to know since such little has been published on his life. I should collect more information from surviving relatives. Some clues might be found in Tanagras' unpublished autobiography, which he sent to the Elliot Garrett Parapsychology Foundation Library in New York. The library is in Long Island, and I would love to visit it. I also hope to communicate with Fotini Pallikari, the scholarly expert on Tanagras. My cousin Angelos (named after Tanagras) Vallianatos is the official family historian; we've just connected on Facebook and I hope to talk to him more about this legendary great uncle when I travel to Greece this summer.

Tuesday, January 27, 2009

Angelos Tanagras

William Caraher has been researching the relationship between dreams and archaeology, specifically how visions have assisted the discovery of new sites. This is an ancient trope that Caraher has been tracing through Late Antiquity, Byzantium and Greek folklore. His research has taken a turn towards psychoanalysis and the figure of Angelos Tanagras, the Greek pioneer in psycho-physical studies. Tanagras happens to be my great uncle, the brother of Katerina Bravos, my maternal grandmother. My mother and aunts were extremely close to Tanagras, he was their closest thing to a father figure. He died when I was only five years old so I do not remember him well, but my mother and aunts always talked to me about him with curiosity and admiration. For today's posting, I will give a general overview of Tanagras' career to the degree that I have been able to reconstruct it. This might be helpful, since so little is available in English. In future postings, I want to make some speculative connections between Tanagras and archaeology, directly responding to Caraher's research.

William Caraher has been researching the relationship between dreams and archaeology, specifically how visions have assisted the discovery of new sites. This is an ancient trope that Caraher has been tracing through Late Antiquity, Byzantium and Greek folklore. His research has taken a turn towards psychoanalysis and the figure of Angelos Tanagras, the Greek pioneer in psycho-physical studies. Tanagras happens to be my great uncle, the brother of Katerina Bravos, my maternal grandmother. My mother and aunts were extremely close to Tanagras, he was their closest thing to a father figure. He died when I was only five years old so I do not remember him well, but my mother and aunts always talked to me about him with curiosity and admiration. For today's posting, I will give a general overview of Tanagras' career to the degree that I have been able to reconstruct it. This might be helpful, since so little is available in English. In future postings, I want to make some speculative connections between Tanagras and archaeology, directly responding to Caraher's research.Angelos Euangelidou was born in Athens in 1877. The name Tanagras is a literary pseudonym that he created for himself, surely based on the romantic associations of the Tanagra figurines (19th-c. archaeological discovery in Boeotia). Tanagras studied medicine at the University of Athens and pursued graduate studies in Berlin. He joined the Greek Navy in 1897, and fought in the Greek-Turkish war. He organized the health standard of Piraeus' port and an infectious disease center on the island of Salamina. He fought in the First Balkan War (1912-13) and World War I. During the 1922 destruction of Smyrna, he became public health supervisor of the International Committee of Asia Minor, organizing the city's health standards. He retired from the navy as Admiral and as Chief Health Commissioner.

His research and consequent claim to fame, however, was not directed on the physical body but on the psyche. Starting with his psychoanalytical research in Germany, he became a leading authority in the causality between psychic and physical phenomena. In 1923, he founded the first Greek psychological society, the Society of Psychic Research, that pioneered the study of paranormal phenomena. He published the journal Psychic Research. In 1930, he organized a very important meeting in Athens, the 4th International Congress of Psychic Research. His theories of "psycho-projection" were first published in Berlin (Zeitschrift für

Sunday, January 25, 2009

Cypriot Tomb Scratchings

Tassos Papacostas' monograph-article, "The History and Architecture of the Monastery of Saint John Chrysostomos at Koutsovendis, Cyprus, Dumbarton Oaks Papers 61 (2007) pp. 25-148, reprints a photograph by Cyril Mango from a medieval tomb slab (fig. 28), first published in Dumbarton Oaks 44 (1990) fig. 186. On the left, I have sketched out the general elements of the slab. The lines on the upper left represent the entombed human. The figure is drawn so scantily and reminds me of medieval graffiti. A couple of additional lines, moreover, add complexity to the reading of the piece. First, there are drilled holes parallel to the oval that frames the figure. Scratchings inscribing an arc across the slab suggest the slab's placement under a swinging door, a threshold (whether of primary or secondary setting). A clef-like symbol tops the upper right edge. The vertical lines are cuts along the slab.

Tassos Papacostas' monograph-article, "The History and Architecture of the Monastery of Saint John Chrysostomos at Koutsovendis, Cyprus, Dumbarton Oaks Papers 61 (2007) pp. 25-148, reprints a photograph by Cyril Mango from a medieval tomb slab (fig. 28), first published in Dumbarton Oaks 44 (1990) fig. 186. On the left, I have sketched out the general elements of the slab. The lines on the upper left represent the entombed human. The figure is drawn so scantily and reminds me of medieval graffiti. A couple of additional lines, moreover, add complexity to the reading of the piece. First, there are drilled holes parallel to the oval that frames the figure. Scratchings inscribing an arc across the slab suggest the slab's placement under a swinging door, a threshold (whether of primary or secondary setting). A clef-like symbol tops the upper right edge. The vertical lines are cuts along the slab.Isn't this a puzzling image? Its haphazard (dare, I say) vernacular character introduces questions about the nature of funerary demarcation in the Byzantine and Latin Middle Ages. Is a childlike scratching sufficient to outline the bodily character of the deceased, lying below? Is the funerary image simply indexical, pointing a finger to the body underneath the slab? In order to place the slab in context, I have followed the comparanda in Brunehilde Imhaus' authoritative catalog of Cypriot funerary inscriptions, Lacrimae Cypriae: Les lamres de Chypre, 2 vols. (Nicosa, 2004). This is a spectacular publication. I am pouring over the 564 comparative pieces, relishing in the beautiful combination of clothed human figures, insignia and text.

The examples from Lacrimae Cypriae, however, are much more articulated. Consider the figure on the left, (no. 166, v. 1, pp. 87-89, pl. 78), the tomb of a knight from the Cathedral of Saint Sophia, dating to 1370. The inscription identifies the figure as Messire Ansiau de Moustazou. Although carved with incisions similar to the Koutsovendi slab, the iconography is elaborate. We can identify a full figure whose features (face, hair) are stylized to fit the elaborated dress (chain link, armor, shield). The composition is framed by a Gothic triangle with floral decorations and heraldic shields. Around the iconic field we have a Latin insciption wrapping around the edges of the slab.

The examples from Lacrimae Cypriae, however, are much more articulated. Consider the figure on the left, (no. 166, v. 1, pp. 87-89, pl. 78), the tomb of a knight from the Cathedral of Saint Sophia, dating to 1370. The inscription identifies the figure as Messire Ansiau de Moustazou. Although carved with incisions similar to the Koutsovendi slab, the iconography is elaborate. We can identify a full figure whose features (face, hair) are stylized to fit the elaborated dress (chain link, armor, shield). The composition is framed by a Gothic triangle with floral decorations and heraldic shields. Around the iconic field we have a Latin insciption wrapping around the edges of the slab.Compositionally, we are in safe art-historical territory and can say lots about iconography, status, identity, and style. Although found in a provincial setting, the slab derives from a rich tradition of medieval funerary art that depicts full bodies. For a comparable crusader example, see tomb of William of Saint John, Archbishop of Nazzareth, from Acre, illustrated in Jaroslav Folda's, Crusader Art in the Holy Land: From the Third Crusade to the Fall of Acre 1187-1291 (Cambridge, 2005), p. 495, fig. 337. These inscribed slabs are related to the graphic techniques of manuscript illuminations. Other tombs pop out into the third dimension; one of my favorites such sculptures is a recumbant knight from Normandy (ca. 1220-1240) at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. The art historical context shows a range of representation, from three-dimensional physicallity to two-dimensional stylization. In lacking elaborate artifice, the slab of Koutsovendis disrupts our expectations of beauty. Whether talismanic, cartoonish, accidental, or uniconic, the slab expands the margins of what the medieval viewer of Cyprus would find acceptable for monumental, public commemoration.

I must stress that I have NOT seen the original piece, so my observations here are very tangential, perhaps fitting the incomprehensible character of the piece. Nor am I an expert on Lusignan Cyprus. Superficially, the slab connects to a body of haphazard visual notations that I've collected from Corinth and other Byzantine sites. See discussion on graffiti and street art in this blog.

Tuesday, January 20, 2009

The Inauguration

I have been glued on the TV all day watching the inauguration of Barak Obama. Tomorrow, I start my history of architecture class at Connecticut and I am simply overwhelmed with the richness of America's architectural tradition unfolding in front of the television. From Saint John's Episcopal Church (Benjamin Latrobe, 1815), and the Capitol Building (William Thornton, Benjamin Latrobe, Charles Bulfinch, William Strickland, 1791-1863), its Statuary Hall and its featured painting View of the Yosemite Valley by Thomas Hill (on loan from the New York Historical Society), to the Beaux Arts buildings on Pennsylvania Avenue swarming with people, The Old Post Office Pavilion (Willoughby Edbrook, 1880), the National Gallery East Building (I.M. Pei, 1968), the Canadian Embassy (Arthur Erickson, 1989), the White House (Benjamin Latrobe, 1801), its Miesian viewing stand, the Washington Monument (Robert Mills, 1848) and, of course, the Lincoln Memorial (Henry Bacon, 1922), the most central building in Barack Obama's architectural iconography, see Democratic Classicism post.

I have been glued on the TV all day watching the inauguration of Barak Obama. Tomorrow, I start my history of architecture class at Connecticut and I am simply overwhelmed with the richness of America's architectural tradition unfolding in front of the television. From Saint John's Episcopal Church (Benjamin Latrobe, 1815), and the Capitol Building (William Thornton, Benjamin Latrobe, Charles Bulfinch, William Strickland, 1791-1863), its Statuary Hall and its featured painting View of the Yosemite Valley by Thomas Hill (on loan from the New York Historical Society), to the Beaux Arts buildings on Pennsylvania Avenue swarming with people, The Old Post Office Pavilion (Willoughby Edbrook, 1880), the National Gallery East Building (I.M. Pei, 1968), the Canadian Embassy (Arthur Erickson, 1989), the White House (Benjamin Latrobe, 1801), its Miesian viewing stand, the Washington Monument (Robert Mills, 1848) and, of course, the Lincoln Memorial (Henry Bacon, 1922), the most central building in Barack Obama's architectural iconography, see Democratic Classicism post.Emotionally overwhelmed by the momentous event, I turn now inward and confront my own civic responsibilities. How can I contribute to the Change heralded by Obama's presidency? Re-reading Howard Zinn, People's History of the United States: 1492-Present, was the first thing that came to mind for guidance. But ultimately, I feel my commitment is to teach through architectural history. I set my first goal as follows. To give my students the necessary vocabulary so that they could truly understand how radically different the White House is from the Lincoln Memorial, even though superficially they seem similarly traditional. I am afraid that the nuances of Washington's architecture was lost to most viewers because it has been generically labeled "all American." Perhaps here I can make a modest contribution. Two weekends ago, I gave a walking tour "Archaeology into Architecture" for the Annual Meetings of the Archaeological Institute of America in Philadelphia. The attendants were all non-specialists. For 2 1/2 hours we traveled across American history, from the colonial Independence Hall to the modern PFSF Building, showing the consecutive but radically different archaeological inspirations for each of the various American styles. We also visited the 2003 excavations of the slave quarters behind the President's House, published in Rebecca Yamin's Digging in the City of Brotherly Love: Stories from Philadelphia Archaeology (2008). Perhaps change can come through architectural knowledge and archaeological discipline.

My favorite images from the Inauguration festivities came from two days ago, with Bruce Springsteen performing "We Are One" at the Lincoln Memorial, flanked by its Doric colonnade and a red gospel choir. The image (above) was published in the New York Times (January 19, 2009, p. C1). I have some hope in these white columns, at least in as much as they can be understood. Let's look beyond the iconic and understand the substance.

Monday, January 19, 2009

Teaching Thursday: Architecture 1400-Present

Teaching Thursday is around the corner. I am teaching a new class at Connecticut College, a history of architecture from the Renaissance to the present. I have taught variations of architecture surveys, trying out different approaches, textbooks and strategies. This time around, I am focusing on what I am slowly realizing is a deficit in the skill-set of art history or architectural studies undergraduates. Students seem to be less and less capable of comprehending abstraction. In the age of High Modernism, the ability to comprehend formal relationships was central. But in the age of Postmodernism, narrative seems to have taken over. This has hurt architectural discourse, not only in undergraduates but also in the general public. And I don't mean abstraction as simply geometrical thinking in modernism or the Renaissance; I mean abstract relationships, an ability to look at an image (let's say a facade) and be able to read things that are less obviously visible (decoration, or lack thereof).

Teaching Thursday is around the corner. I am teaching a new class at Connecticut College, a history of architecture from the Renaissance to the present. I have taught variations of architecture surveys, trying out different approaches, textbooks and strategies. This time around, I am focusing on what I am slowly realizing is a deficit in the skill-set of art history or architectural studies undergraduates. Students seem to be less and less capable of comprehending abstraction. In the age of High Modernism, the ability to comprehend formal relationships was central. But in the age of Postmodernism, narrative seems to have taken over. This has hurt architectural discourse, not only in undergraduates but also in the general public. And I don't mean abstraction as simply geometrical thinking in modernism or the Renaissance; I mean abstract relationships, an ability to look at an image (let's say a facade) and be able to read things that are less obviously visible (decoration, or lack thereof).I believe that part of this abstraction-illiteracy in architectural education has to do with a general lack of attention to the late 18th and early 19th centuries. Renaissance and Baroque are taught in their obvious humanistic dimensions between abstraction and beauty, but then we tend to sweep over the 18th and 19th centuries as the age of historicism that is ultimately superseded by the age of a-historicism, pure form and functional modernity. In the process, we have undermined the Enlightenment, which holds the key to understanding the complexity of everything to follow. This realization was further compounded while watching the HBO series John Adams that recreates the foundation of the United States. We think we know American history, but actually, the intellectual context of American Revolution is just as foreign to undergraduates as the more exotic new (but ultimately old) fascination with Asia and the Middle East. I don't want to sound like one of the fashionable "neo-humanists" like Christopher Hitchens, but the Enlightenment has been forgotten. Can a student look at Jefferson's Monticello and see pure reason or a debate on the status of inalienable rights? My goal is to have students understand that some old things are radical, although they may look identical to some other things that are banal. We'll see if my strategy works. Will a guided focus on Boullee's paper architecture, or the Gothic revival of Pugin and Ruskin enlighten Palladio and Brunelleschi (in one direction) and Le Corbusier and Mies (in the other direction)?

My architecture survey class, therefore, will shorten the obviously beautiful Renaissance and Baroque and give more attention to the Enlightenment and the 19th century. This reflects how I was taught modern history as an undergraduate by David Brownlee at UPenn. Brownlee's two-semester survey of Modern Architecture is devoted entirely to the 18th and 19th centuries, rather than rushing to the modern heroes of the 20th century (that follow in the consecutive semester). If it weren't for Brownlee's unique survey, I would have never decided to become an architectural historian. My research on the historiography of architecture has taken me back to those roots. It's time to put the pre-20th-century architectural historians to the forefront. The writings of David Brownlee, Barry Bergdoll, David van Zanten, Harry Mallgrave and Michael Lewis seem more critical than ever. My sense is that architectural history is slowly truncated from the curriculum, even in architecture programs. This has resulted in more focus on contemporary debates (the theories of postmodernism) and the further historization of modernism. The 18th and 19th century foundations have fallen on the wayside.

So, here is how I am re-tooling my own survey which I have taught almost uninterruptedly since 2002 (at UPenn. Swarthmore, Arcadia and Clemson). First, I am abandoning the traditional mega-textbooks, Marvin Trachtenberg's Architecture: From Prehistory to Postmodernity and Spiro Kostoff's A History of Architecture. As much as I appreciate Kostoff's global perspective, I've found it impossible to use as a textbook. Trachtenberg had been my favorite for its sophisticated language, but it works better in an audience of majors; plus I wouldn't make students buy a $100+ textbook and only use half of it. Instead, I'm trying out two textbooks from the Oxford History of Art series, Berry Bergdoll's European Architecture 1750-1890 and Alan Colquhoun's Modern Architecture. These are supplemented by a few chapters from Leland Roth's Understanding Architecture: Its Elements, History, and Meaning. I have never taught Bergdoll before, but I found it to be one of the best introductions of early modernity. Colquhoun is perhaps better appreciated by a generation of architects and theorists than by historians. What I like in Colquhoun is the shortness of the chapters that allow for supplementary readings. On its own, it does not work with undergraduates as well as William Curtis' Modern Architecture since 1900, which is less stingy with the historical context (and thus longer).

In hoping to teach students about abstraction, I am also reviving an old tool, the architect's notebook, where I force the students to take class notes, write diary entries and sketch in the same notebook. This works best with architecture majors, many of whom are registered for my class. I haven't tried the architect's notebook since I taught architecture majors in Philadelphia. New developments in internet surfing (during class), short attention spans, etc. have made note-taking less rigorous of a practice. By collecting notebooks every week, I hope to teach the students not only how to take good notes, but also how to integrate drawings with text.

As it stands, here is my syllabus

Architecture, 1400-Present

Connecticut College, AHI 123-1, Spring 2009

Dr. Kostis Kourelis

_____________________________________________________________________________________

Class: MW 10:25-11:40 am, Cummings 308

Office hours: W 12 pm- 2 pm, Cummings 210

Email: kkourelis@gmail.com

COURSE DESCRIPTION

Architecture from the Italian Renaissance in the 15th century to critiques of Modernism in the post-World War II period, considered in the context of social, cultural, economic, and political developments. Emphasis on Europe and the United States, with attention to urbanism and landscape architecture.

The course aims to give a thorough understanding of architectural discourse from its origins in the Renaissance to its collapse in the age of “post-criticism.” In addition to learning the parade of styles and architectural innovations, we will consider the art of building as the highest form of human inquiry. In order to fully appreciate the depths of architectural meaning, we must situate each period in its appropriate sociological and theoretical context. Most importantly we must learn how to read the language of architecture, its parts, inherent qualities, contradictions and formal principles. But we will also read some published treatises, where architects themselves articulate their highest ideals in words and drawings.

REQUIREMENTS

We are covering such a huge span of history that every detail counts. You will memorize the most important buildings and will be called to relate them to each other. Half of the grade will be based on a midterm and a final exam that will involve identifying monuments, architects, movements and writing critically. Following an old tradition of the Architectural Notebook, you will be asked to keep a notebook dedicated to class notes, drawings, analysis and weekly exercises. The notebook will be collected every week and graded.

Grading: Final Exam 30%, Midterm Exam 20%, Notebook 50%

TEXTBOOKS

Barry Bergdoll, European Architecture 1750-1850 (Oxford, 2000), at bookstore

Alan Colquhoun, Modern Architecture (Oxford, 2002), at bookstore

Leland M. Roth, Understanding Architecture: Its Elements, History, and Meaning (Boulder, 2007), PDF files

Samples of architectural treatises, PDF files

READING SCHEDULE

Jan 21 Introduction

Jan 26 The Renaissance Roth ch. 15, pp. 352-376

Jan 28 Palace, Villa, Mannerism Roth ch. 15, pp. 376-385

Feb 2 Baroque Roth ch. 16, pp. 397-415

Feb 4 Neoclassicism and Reason Bergdoll, ch. 1, pp. 9-23

Feb 9 Neoclassicism and History Bergdoll, ch. 1, pp. 33-41

Feb 11 The Picturesque Bergdoll, ch. 3, pp. 73-85

Feb 16 Revolutionary Architecture Bergdoll, ch. 3, pp. 86-102

Feb 18 The Gothic Revival Bergdoll, ch. 5, pp. 139-167

Feb 23 Romantic Historicism Bergdoll, ch. 6, pp. 173-200

Feb 25 New Technologies Bergdoll, ch. 7, pp. 207-238

Mar 2 The City Bergdoll, ch. 8, pp. 241-267

Mar 4 Midterm Exam

-------- Spring Break

Mar 23 Art Nouveau Colquhoun, ch. 1, pp. 13-33

Mar 25 The Chicago School Colquhoun, ch. 2, pp. 35-55

Mar 30 Culture and Industry Colquhoun, ch. 3, pp. 57-71

Apr 1 Expressionism and Futurism Colquhoun, ch. 5, pp. 87-107

Apr 6 De Stijl and Constructivism Colquhoun, ch. 6, pp. 109-135

Apr 8 Le Corbusier Colquhoun, ch. 7, pp. 137-157

Apr 13 The Bauhaus Colquhoun, ch. 8, pp. 159-170

Apr 15 Mies van der Rohe Colquhoun, ch. 8, pp. 170-181

Apr 20 Italian and Scandinavian Modern Colquhoun, chs. 9 & 10, pp. 183-194, 200-204

Apr 2 American Modern: Art Deco

Apr 27 Monumentality and Critique Colquhoun, ch. 11, pp. 209-229

Apr 29 Pax Americana Colquhoun, ch. 12, pp. 231-254

May 4 Late Modernism Roth, ch. 20, pp. 567-590

May 6 Postmodernism Roth, ch. 20, pp. 591-612

Wednesday, January 14, 2009

The Turtledove

Greek folk culture can be a far cry from Victorian niceties. Some of its themes and imageries can be outright shocking, brutal and surreal. But this, of course, can be said about many pre-modern folk traditions (think of the American "Pretty Polly"). In 1927, folklorist Georgios Megas published a collection of Greek children stories, Παραμύθια, illustrated by Photes Kontoglou. Ellenika Paramythia has been reprinted many time; the latest, 7th edition is still available at Estia publishing house and bookstore. An English translation, Folktales of Greece, was published in 1970 (Chicago University Press). Four years ago, when my niece was born, I bought her a copy. Kristina is now old enough to have Greek folk tales read to her and my sister is going through the collection. Both have realized, however, that compared to Dr. Seuss, the Green Caterpillar, or Goodnight Moon, Greek folktales can keep you up at night with nightmares.

Greek folk culture can be a far cry from Victorian niceties. Some of its themes and imageries can be outright shocking, brutal and surreal. But this, of course, can be said about many pre-modern folk traditions (think of the American "Pretty Polly"). In 1927, folklorist Georgios Megas published a collection of Greek children stories, Παραμύθια, illustrated by Photes Kontoglou. Ellenika Paramythia has been reprinted many time; the latest, 7th edition is still available at Estia publishing house and bookstore. An English translation, Folktales of Greece, was published in 1970 (Chicago University Press). Four years ago, when my niece was born, I bought her a copy. Kristina is now old enough to have Greek folk tales read to her and my sister is going through the collection. Both have realized, however, that compared to Dr. Seuss, the Green Caterpillar, or Goodnight Moon, Greek folktales can keep you up at night with nightmares.Last week, I wrote about a sexually charged lullaby that my grandmother sang to my sister in 1967, the Partridge. To see the function of another bird in a 19th century folksong from Nauplion, see "Lady 'Reen, the Little Bird, and the Pirate," in Surprised by Time. The bird here tells of incest. Seeking lullabies for my own daughter, I am thankful to my koumpara Anna Androulaki for sending The Great North Wind and other Traditional Songs for Children, a compilation by Domna Samiou, who is a monumental figure in Greek folk music as both interpreter and folklorist. She is the Alan Lomax of Greece. I first saw Samiou perform on the steps of the Gennadius Library in 1999, as a fellow at the American School. Harris Kalliga, director of the Gennadius at the time, had invited Samiou to perform. Looking back at the festivities, I wonder how many American students appreciated the concert. Many faculty and students, I remember, danced their hearts out, including Ioulia Tzonou-Herbst, the best Greek-dancer of the School.

In Samiou's 2-CD collection of children songs, we find another bird, Τρυγώνα (Turtledove) from Epeiros. It is a beautiful song, but it's theme, the discovery of a dead corpse, would surely scare the wits of any modern child. Here are the lyrics:

High up upon your way, turtledove,

down low as you pass by, sweet beautiful turtledove,

might you have caught sight

of my beloved, turtledove,

my sweetheart, my dearest man?

"Last night we saw him

or the night before

laid out upon the plane.

Black birds were eating him,

white birds circling above him."

or in Greek,

Αυτού ψηλά που περπατείς, τρυγόνα, μωρή τρυγόνα,

και χαμηλά λογιάζεις, τρυγόνα μου γραμμένη

μην είδες τον ασίκη μου, το άντρα το δικο μου;

-Εψές προψές τον είδαμε στον κάμπο ξαπλωμένο

μαύρα πουλία τον τρώγανε κι άσπρα τον τριγυρνούσαν.

Note how the turtledove is γραμμένη (striped, marked, or fated), same as my grandmother's partridge. Based on a reference in the Song of Songs, the turtledove has been a Judeo-Christian symbol of love. We find it in many English and American folk songs of loss of love; see, William Shakespeare's "The Phoenix and the Turtle."

Tuesday, January 06, 2009

Peloponnesiaca

And I remembered a paper that Wright presented at the 30th Byzantine Studies Conference in Baltimore, "Was William of Moerbeke an Angevin Agent?"It's a fabulous piece of scholarship linking geopolitical agendas with antiquarianism. As far as I know, the paper is unpublished. I also wish I had been in Athens to see Wright's lecture, "Ottoman Venetian Cooperation in Post-War (1463-1478) Morea" (November 25, 2008). I'm also reminded of a paper that Siriol Davies gave a few years ago about a new discovery of a Venetian map in a Vienna. This map shows explicit classical antiquarian interests in the Venetian occupation of the Peloponnese. (I'll have to dig up the reference). Many thanks also to Guy Sanders and to Mary Lee Coulson, who have made Merbaka central to our scholarly concerns.

Going back to Cyriacus, I cannot help but share my favorite Cyriacus passage, where he describes the state of ancient cities as he rides by them. While visiting his fellow humanist Plethon at Mystras in 1448, Cyriacus inspected

"While contemplating en route from afar the ruins of once-famous Laconian towns, mulling this over in my mind, I thought, naturally, of that fact that, even though one must grieve to behold these noble, ancient, distinguished and richly adorned cities, now in our time in a state of utter collapse or demolition almost everywhere throughout the region, one must endure with an [even] heavier heart, in my opinion, the pitiable ruin of the human race, because the fact that the world’s outstanding towns, marvelous temples sacred to the gods, beautiful statues and other extraordinary trappings of human power and skill have fallen from the pristine grandeur seems not so serious as the fact that, throughout almost all the regions of the world, the pristine human virtue and renowned integrity of spirit has fallen into an [even] worse condition; and where they had once flourished most, there they had more and more departed."

The Renaissance antiquarian witnessed a landscape of devastation and abandonment, scarred by the neglect of time but also by wars, civil strife and plague. Seeing the ruins inspired lament for the loss of classical culture and the ideals it represented. Cyriacus’ countryside instructs in humility and virtue and offers a new interpretive paradigm. A. T. Grove and O. Rakcham have argued that Cyriacus' point of view was partially created by the perceptible difference between the Italian and Greek landscapes, see Mediterranean

The 2007 issue of Dumbarton Oaks Papers is a great issue for the archaeologist because it contains essays from the 2005 Symposium "Settlement Patterns in Anatolia and the Levant: New Evidence from Archaeology." In addition it contains a book-length article by Tassos Papacostas, "The History and Architecture of the Monastery of Saint John Chrysostomos at Koutsovendis, Cyprus," pp. 25-148 and the most recent excavation report from Amorium.

Monday, January 05, 2009

More Trahanas

I remain optimistic about the survival of Greece's culinary tradition into the 21st century without it becoming elitist, the way that French and Italian (but not Spanish or Central European) cuisines have been commodified. Greece has been rediscovering its culinary past that was twice flattened in the 1920s and in the 1950s. The first suppresion began in 1910 with Nikolaos Tselementes' publication of the first cookbook written for an audience of urbanized housewives. This is typical to the genre internationally; cookbooks become important only after the oral transmission from generation to generation is under threat. Down to this day, the word "tselementes" in Greeks means "cookbook." Like the linguistic katharevousa, Tselementes purified Greek cooking from traces of Ottomaness by injecting Frenchness. Mousaka and pastitsio came into being, dishes lavishly covered with the uber-French bechamel cream sauce. The second flattening occurred in the 1950s with mass tourism and the need to export a manufactured Greek essence. Tourists arrived with specific dishes in mind, and Greek restauranters (many of whom only served foreign crowds) provided in unitary flare. The wave of culinary rediscovery can be seen in the revival of ouzeries, accompanied by a new focus on Greek wines, and oinothekes. The Greek wine craze seems to have evern caught up in the United States, see Eric Azimov, "Wines of the Times: Crisp, Refreshing and Greek," New York Times (Aug. 6, 2008). Food writers Aglaia Kremezi and Diane Kochilas are the best guides for the Greek food renaissance that Tselementes and tourism once suppresed. Kochilas, a Greek American, shows the cultural depth of the Greek omogeneia.

Going back to trahanas, I would like to share a comment that Nassos Papalexandrou sent to me via email. I know Nassos through Amy Papalexandrou (a fellow classicist-Byzantinist plus trans-national couple). It was by great surprise to learn last summer that Nassos' maternal family is from the same region as my paternal family. In other words, we are symptatriotes. Nassos is a professor of Classics at UT Austin and has just written a wonderful essay on a Cypriot mosque, see "Hala Sultan Tekke, Cyprus: An Elusive Landscape of Sacredness in a Liminal Context," Journal of Modern Greek Studies 26 (2008) 251-281. Bill Caraher's blog brought this article to my attention.

From Nassos Papalexandrou

papalex@mail.utexas.edu

January 2, 2009

"Re. Trahanas: your piece brought up lots of my childhood memories: in my mother's place, also in Fthiotis (now: Pelasgia formerly Gardiki Kremastis Larissis), the annual making of Trahanas was a communal undertaking (precisely like making soap or chilopittes), with several women getting together, sharing labor, tools (e.g. the cauldron, "kazani"), materials, and the end product: I relished the still wet pieces, creamy and very tasteful, as they were laid out to dry and very often I earned my samplings by playing guard against cats and other interested predators. In my father's place, in Bardounia of Lakedaimon (Petrina, also known for its Paleologan tower-"o pyrgos tou Koutoupi" with which I presume you are very familiar) , they make a different king of Trahana: they fry it so that it makes a pudding-like substance (like deep fried beans) which is sweet and sour at the same time. The Stereoelladitiko makes great soup (my mom still calls it "chelos"), especially when cooked with chicken or in chicken stock instead of water--do try it with a bit of tomato (my mother's version of "comfort food") !!!!"

papalex@mail.utexas.edu

January 13, 2009

Saturday, January 03, 2009

The Partridge

In 1967, my grandmother Afendra Kourelis came to Athens for a short visit with my parents, who just had their first baby, my sister Afendra (or Angeliki). Giagia Afendra was raised in Leukada, a small agricultural village in Fthiotis, in continental Greece (Sterea Ellada). One of the treasures that she brought along from the village were folk lullabies she sang to her baby granddaughter, no doubt the very same tunes she sang on my father's bedside back in 1929, when my father was born. Mid-60s Athens was a booming metropolis, but my grandmother hated the city and could not wait to return to her fields. But modern Athens offered new media like television, film, phonograph records and tape recorders. My father did an amazing thing at that moment, to record his mother's lullabies. My father's obsession with recording sound is itself an interesting topic for another posting. I found the reel-to-reel tape a couple of years ago and transcribed it into a CD, which I am now going through closely in order to lern the songs and, in turn, sing them to my own infant daughter. The whole experience has been incredibly moving, listening to a woman born in 19th-century Greece. My infant sister is making baby sounds, while my parents (both deceased) are engaging with her in silly ways. It is also fascinating to hear my father, who was born and raised in Leukada but became totally urbanized as a teenager. While encouraging his mother to sing more of those old songs, he flips into the local dialect, a different voice from the one we grew up with. The songs were recorded in a small apartment in the neighborhood of Kypseli. My sister's childhood photo album contains a picture of this very visit, with a grandmother wrapped in her black tsemperi, sitting royally in a tight balcony.

In 1967, my grandmother Afendra Kourelis came to Athens for a short visit with my parents, who just had their first baby, my sister Afendra (or Angeliki). Giagia Afendra was raised in Leukada, a small agricultural village in Fthiotis, in continental Greece (Sterea Ellada). One of the treasures that she brought along from the village were folk lullabies she sang to her baby granddaughter, no doubt the very same tunes she sang on my father's bedside back in 1929, when my father was born. Mid-60s Athens was a booming metropolis, but my grandmother hated the city and could not wait to return to her fields. But modern Athens offered new media like television, film, phonograph records and tape recorders. My father did an amazing thing at that moment, to record his mother's lullabies. My father's obsession with recording sound is itself an interesting topic for another posting. I found the reel-to-reel tape a couple of years ago and transcribed it into a CD, which I am now going through closely in order to lern the songs and, in turn, sing them to my own infant daughter. The whole experience has been incredibly moving, listening to a woman born in 19th-century Greece. My infant sister is making baby sounds, while my parents (both deceased) are engaging with her in silly ways. It is also fascinating to hear my father, who was born and raised in Leukada but became totally urbanized as a teenager. While encouraging his mother to sing more of those old songs, he flips into the local dialect, a different voice from the one we grew up with. The songs were recorded in a small apartment in the neighborhood of Kypseli. My sister's childhood photo album contains a picture of this very visit, with a grandmother wrapped in her black tsemperi, sitting royally in a tight balcony.Some of Afendras' songs are difficult to decipher because of the thick Sterea Ellada dialect. Among the discernible tracks is the song of the Marked, or Striped Partridge. I transcribe my grandmother's lyrics below, trying to be faithful to all the words, even the ones that I don't undrestand (like the "mo" and "mari" insertions).

Που ήσαν πε μαρί πέρδικα

που ήσαν πέρδικα γραμμένη

κι ήρθες το πρωί βρεμένη

Ναι μανί μαρί πέρδικα

ναι μανί ψηλά στα πλάγια

στις δροσιές και στα χορτάρια

Κι έτρωγα μαρί πέρδικα μω

κι έτρωγα το μαντριφύλι

κυδωναύγουστο σταφύλι

Where were you partridge?

Where were you, you marked partridge

that, in the morning, you returned all wet?

Yes, said the partridge

I went to the high slopes

where there is dew and grass

And I ate

I ate the clover by the sheepfolds

and the quince-like grape of August

The song is amazing in many ways, and I have not gone through any close linguistic or symbolic readings. I know that in Byzantine literature, the partridge symbolized the church and fidelity but also temptation and betrayal (see, 14th-c bird epic, Πουλολόγος, etc.) To me, the song has clear sexual connotations; the partridge returns all wet having tasted some forbidden fruit. The wonderful thing about Greek folk songs is an ambiguity that leads to multiple readings. In the context of an infant, the wet partridge stops being sexual and becomes a metaphor for the baby that wetted itself overnight having traveled to idyllic dream-lands.

I also love the way that the partridge is described as "γραμμένη," which literally means "written," but refers to the "γραμμές," the lines that marked its body. Alectoris graeca, the partridge indigenous to Greece, has beautiful black stripes on its wings. In English it is known as Rock Partridge. The partridge, moreover, has a beautiful voice and is, thus, a worthy model for the crooning singer. Alcman, the Archaic poet from Sparta, for instance, learned his poetic skills from partridges. To call a partridge "γραμμένη" also adds an element of inevitability, the participle form also means "fated," as in "it has been written." My friend Nassos Papalexandrou, whosε family is from the same region as mine, tells me that his mother still uses the word "γραμμένη" to describe the beauty of well shaped facial features, like eyes and lips.

Thursday, January 01, 2009

Domestic Archaeology: House of the Rising Sun

The House of the Rising Sun is one of the best known rock songs, a landmark across many genres: American blues and folk, the British Invasion, garage rock and even punk. Its origins are complicated and contested; people still argue whether it was Woody Guthrie, Bob Dylan, or The Animals who ushered the song into the popular mainstream. It probably dates to 18th-century American folk tradition but entered ethnographic fact on September 15, 1937, when folklorist Alan Lomax taped a 16-year-old miner's daughter, Georgia Turner, performing the song in Middlesborough, Kentucky. Since then, many have rendered their own versions, from Roy Acuff (1937), Woody Guthrie (1941), Lead Belly (1948), Glenn Yarbrough (1957), to Bob Dylan (1961). The song, however, did not become a classic until 1964, when the The Animals from Newcastle, Britain made it into a number one hit.

The House of the Rising Sun is one of the best known rock songs, a landmark across many genres: American blues and folk, the British Invasion, garage rock and even punk. Its origins are complicated and contested; people still argue whether it was Woody Guthrie, Bob Dylan, or The Animals who ushered the song into the popular mainstream. It probably dates to 18th-century American folk tradition but entered ethnographic fact on September 15, 1937, when folklorist Alan Lomax taped a 16-year-old miner's daughter, Georgia Turner, performing the song in Middlesborough, Kentucky. Since then, many have rendered their own versions, from Roy Acuff (1937), Woody Guthrie (1941), Lead Belly (1948), Glenn Yarbrough (1957), to Bob Dylan (1961). The song, however, did not become a classic until 1964, when the The Animals from Newcastle, Britain made it into a number one hit.The song refers to a New Orleans house of prostitution with a contested archaeological history. Some claim that 826-830 Louis Street is the original location of the house, originating from the name Marianne LeSoliel Levant, the brothel's Madam from 1862 to 1874. There is no proof of this lineage. An 1838 newspaper mentions a Rising Sun coffee house on Decatur Street, and a Rising Sun hotel stood on Conti Street before it burned down in 1822. The latter site was the subject of a 2004 excavation by Shannon Lee Dawdy, now assistant professor of archaeology at the University of Chicago. Dawdy could not conclusively prove whether this was the famous House of the Rising Sun. For Dawdy's fascinating work after Katrina, see John Schwarts, "Shannon Lee Dawdy: Archaeologist in New Orleans Finds a Way to Help the Living," New York Times (Jan. 3, 2006).

More interesting than the song's real archaeology is its idealized archaeological projection. The Animals performed their number one hit in the 1965 music film Pop Gear, surrounded by a fantasized archaeological cage, stripped down in groovy mid-modern minimalism. The clip (seen here) is absolutely stunning. The artistic level of its production is so superior that it makes one wonder what happened to the integration between popular music and the visual arts.

The set design is based on an Ionic colonnade built by purely white thin boards through which The Animals circumnavigate. A yellow wall (matching the band's shirts, beneath their 4-button suits) forms the background and receives both the white thin columns and their intense gray shadows. I've tried to capture the dynamism of this imagined House of the Rising Sun in a sketch at the beginning, but much of the energy of the video comes from the movement of the mobile musicians (Burdon, Valentine, Chandler) around the stationary musicians (Gallagher, Steel), the close ups on Burdon, and the movement of the camera behind the colonnade providing a peculiar (both thin and thick) sense of depth. The set reconfigures the porch of southern domestic architecture, its classical vocabulary, as well as its papery thinness. The composition, however, is entirely modernist with Cubist composition, Constructivist combinations and an Expressionist sense of light.

The set design is based on an Ionic colonnade built by purely white thin boards through which The Animals circumnavigate. A yellow wall (matching the band's shirts, beneath their 4-button suits) forms the background and receives both the white thin columns and their intense gray shadows. I've tried to capture the dynamism of this imagined House of the Rising Sun in a sketch at the beginning, but much of the energy of the video comes from the movement of the mobile musicians (Burdon, Valentine, Chandler) around the stationary musicians (Gallagher, Steel), the close ups on Burdon, and the movement of the camera behind the colonnade providing a peculiar (both thin and thick) sense of depth. The set reconfigures the porch of southern domestic architecture, its classical vocabulary, as well as its papery thinness. The composition, however, is entirely modernist with Cubist composition, Constructivist combinations and an Expressionist sense of light.The L-shaped elements may also remind us of the hang-man games we played as children and, thus, suggest connotations of lynching. Without a doubt, The Animals were aware of Billy Holiday's Strange Fruit. A fascinating song in its own right, Strange Fruit was written by Abel Meeropol, a Jewish school teacher from the Bronx. Meeropol cited Lawrence Beitler's graphic 1933 photograph (click here) as inspiration for the lyrics, which he published in a school-teacher union magazine in 1936. Holiday performed the song at the first integrated night club in Greenwich Village in 1939. But this is only a slight, if not sublimated reading.

Overall, The Animals' House of the Rising Sun is pure form. Like the British Invasion in general, the clean-cut gentlemen from Newcastle distilled the southern blues, and repackaged them with a sleek force that could bring down the walls. Cleaned up, the House of the Rising Sun stops being an item of ethnographic "authenticity" and becomes pure libidinal force. Much more than the legendary Beatles, Eric Burdon and The Animals offer the building blocks of a raw subversiveness that leads straight to The Clash. One can clearly see that the architectural style of Deconstructivism begins in 1965. Zaha Hadid, Bernard Tschumi, Daniel Liebeskind and other paper-thin superstars suddenly seem derivative. Are The Animals so important? I hope to study more Pop Gear clips and see how other peer groups contributed to punk archaeology. This includes performances by Herman's Hermits, The Four Pennies, Matt Monroe, Billy J. Kramer and the Dakotas and other slightly forgotten pioneers of what we now group under the category of garage rock.

I must thank my 10-year-old nephew Sean Gray for introducing me to Pop Gear inadvertently. Grandparents Terry and Brenda Gray got Sean a guitar for his birthday in July. During the last few months, Sean has become a studious guitar player, giving his first public recital in Albuquerque, of the House of the Rising Sun. He emailed The Animals video to his uncle and aunt, in case they had never heard of the song before. Since I also got a guitar last Christmas (thanks to Terry and Brenda), I have taken up the challenge of the Rising Sun. Sean is much better than me, but Popi is enjoying the finger picking across the classic Am, C, D, F and E7th chords.

My Blog List

Labels

- 1930s (52)

- ASCSA (25)

- Americana (30)

- Athenaica (36)

- Byzantine (69)

- Cinema (11)

- Cities (6)

- Details (22)

- Family (10)

- Food (9)

- Funerary (13)

- Geography (7)

- Greek American (31)

- House Stories (5)

- Houses (15)

- Islamic Philadelphia (11)

- Lancaster (60)

- Letterform (27)

- Literature (27)

- Modern Architecture (109)

- Modern Art (57)

- Modern Greece (103)

- Music (28)

- Peloponnesiaca (33)

- Philadelphia (70)

- Punk Archaeology (38)

- Singular Antiquity (9)

- Street Art (6)

- Teaching Thursday (28)

- Television (3)

Blog Archive

-

▼

2009

(123)

-

▼

Jan 2009

(13)

- Follow the White Marble Road to Halandri

- Tanagras and Kourouniotis

- Teaching Thursday: History of Domestic Architecture

- Tanagras and Archaeology

- Angelos Tanagras

- Cypriot Tomb Scratchings

- The Inauguration

- Teaching Thursday: Architecture 1400-Present

- The Turtledove

- Peloponnesiaca

- More Trahanas

- The Partridge

- Domestic Archaeology: House of the Rising Sun

-

▼

Jan 2009

(13)