Yesterday morning, I gave a paper at the 36th Annual Byzantine Studies Conference. My paper included archaeological data from Athens, Corinth, Chersonesos, Sicily and Egypt and focused on fetuses buried under house floors (not uncommon). The introduction and the conclusion of the paper were formally written but the case studies were extemporaneously presented from the slides. The paper was just the beginning of a longer article that I hope to write soon, but I offer the draft

here. One can cite the paper as, Kostis Kourelis, "Fleshing Out the Byzantine House,"

Byzantine Studies Conference Abstracts 36 (2010) 117-118, where the following text is published. I should also note that this paper originated from this blog, see

Byzantine Children Burials (Aug. 28, 2008). I want to thank all of you who responded in person or by email to that posting. It illustrates for me the value of blogging and the free exchange of ideas.

FLESHING OUT THE BYZANTINE HOUSEABSTRACT

The mutable nature of domestic architecture has guaranteed the disappearance of most houses from the extant material record visible to the architectural historian. Thanks to commemorative and ritual functions, on the other hand, churches survive in greater numbers and are deployed to tell the whole story of Byzantine architecture. Recent efforts to fill this domestic gap have produced a corpus of houses excavated with greater sensitivity towards anthropological rather than formal architectural questions.

New archaeological evidence allows us to, literally, flesh out the Byzantine house through its engagement in precise ecologies, its inclusion of organic matter and even its incorporation of human bodies. A softer archaeological lens reveals soft tissues of domestic architecture less evident under the harder lens of architectural studies. We look at three categories of artifacts. First, we consider the burial of family members within the house floors. Fetus burials from Athens, domestic family tombs from Chersonesos, or hospice burials from Corinth highlight the Byzantine practice of in-house burials. Second, we consider other living forms involved in the construction of Byzantine houses. A geological study of mortar samples from the Peloponnesos reveals the incorporation of organic material in the making of the walls, typically collected from the community’s own trash heaps. Such organic inclusions complement our knowledge of animal sacrifice during foundation rituals. Third, we consider the ecological niches that different Byzantine settlements engage and the environmental exploitation evident in the houses, from the woods used in construction to the woods used in firing the hearths.

If we admit all this organic evidence into the discussion, we can stipulate an anthropological tension between hard and soft architectural entities. Walls, floors and ceilings formed the physical envelope of Byzantine life. Houses prescribed social life (eating, sleeping, working, playing, praying, procreating) but also embodied deceased organic life. Investigating this type of flesh more broadly allows us to challenge our assumptions of architectural meaning in Byzantium. Masonry was not an inert as the modern scholar would have it. Masonry lived, breathed, listened and occasionally spoke.

Houses are a paradigmatic building type that cannot be separated from the processes of developmental psychology. From early childhood, houses articulate the distinction between animate and inanimate powers that culture proceeds to formulate. To use Sigmund Freud’s terminology, our notion of home incorporates its correlate, “the unhomely” or “uncanny.” Contemporary architectural theory has embraced Freud’s canonical essay on (“Unheimlich,” 1925) in the postmodern armature. Marrying the theoretical uncanny with new archaeological data sheds light on the Byzantine house and throws a wrench (perhaps a toy-wrench) into the stony assumptions of Byzantine architectural history.

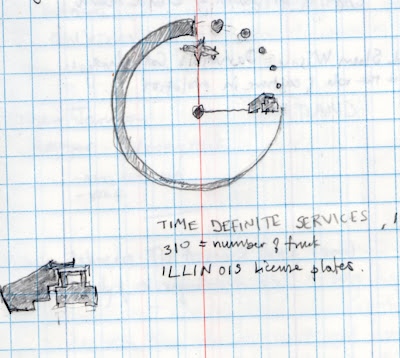

My Powerpoint presentation had 60 slides but, unfortunately, I cannot include it here because much of what I showed is still unpublished. The image above is an Early Byzantine doll excavated in Karanis and now at the Kelsey Museum, see E. Gazda,

Karanis: An Egyptian Town in Roman Times (Ann Arbor, 1983) 29, fig. 52, reprinted in Maguire et al.,

Art and Holy Power in the Early Christian House (Champagne Urbana, 1989) 228, no. 146.

I was thrilled to be included in a wonderful company of papers. The panel was not organized in advance, but was selected from blind abstract submissions. Good job to the program committee and the speakers for a truly thought-provoking morning. Stay tuned because we might be podcasting all the papers.

ARCHITECTURAL SPACE: DOMESTIC, ACOUSTIC, MONASTICSession VIIC: Sunday, Oct. 10, 2010, 9:00-11:30

Chair: Ida Sinkevic (Lafayette College)

Fleshing Out the Byzantine House

Kostis Kourelis (Franklin & Marshall College)

The Past is Noise: Architectural Contexts and the Soundways of Byzantium

Amy Papalexandrou (Austin, TX)

The Materiality of Medieval Monastic Spaces in Egypt

Darlene L. Brooks Hestrom (Wittenberg University)

Cave-Cells and Ascetic Practice in Byzantine and Crusader Paphos

Nikolas Bakirtzis (The Cyprus Institute)

Miracle and Monastic Space: Hermitage of St. Petar of Korisa

Svetlana Smolcic-Mkuljevic (Faculty of IT, Belgrade)

T'was the night before Christmas and all through the house, Not a creature was stirring, not even a mouse.

T'was the night before Christmas and all through the house, Not a creature was stirring, not even a mouse. The stockings were hung by the chimney with care, in hopes that Saint Nicholas soon would be there.

The stockings were hung by the chimney with care, in hopes that Saint Nicholas soon would be there. The children were nestled all snug in their beds. While visions of sugarplums danced in their heads.

The children were nestled all snug in their beds. While visions of sugarplums danced in their heads. And Mamma in her kerchief and I in my cap. Had just settled down for a long winter's nap.

And Mamma in her kerchief and I in my cap. Had just settled down for a long winter's nap. More rapid than eagles his courses they came. And he whistled and shouted, and called them by name: "Now Dasher! Now Dancer! Now Prancer! Now Vixen! On, Comet! On, Cupid! On, Donner and Blitzen! To the top of the porch, to the top of the wall. Now, dash away, dash away, dash away all!

More rapid than eagles his courses they came. And he whistled and shouted, and called them by name: "Now Dasher! Now Dancer! Now Prancer! Now Vixen! On, Comet! On, Cupid! On, Donner and Blitzen! To the top of the porch, to the top of the wall. Now, dash away, dash away, dash away all! The moon on the breast of the new-fallen snow, gave a luster of midday to objects below, when, what to my wondering eyes should appear, but a miniature sleigh and a tiny reindeer; with a little old driver, so lively and quick I knew in a moment it must be St. Nick.

The moon on the breast of the new-fallen snow, gave a luster of midday to objects below, when, what to my wondering eyes should appear, but a miniature sleigh and a tiny reindeer; with a little old driver, so lively and quick I knew in a moment it must be St. Nick. As dry leaves that before the wild hurricane fly,When they meet with an obstacle, mount to the sky, So up to the house-top the courses they flew With a sleigh full of toys, and St. Nicholas too.

As dry leaves that before the wild hurricane fly,When they meet with an obstacle, mount to the sky, So up to the house-top the courses they flew With a sleigh full of toys, and St. Nicholas too. He was chubby and plump, a right jolly old elf. And I laughed when I saw him, in spite of myself. A wink of his eye, and a twist of his head, soon gave me to know I had nothing to dread.

He was chubby and plump, a right jolly old elf. And I laughed when I saw him, in spite of myself. A wink of his eye, and a twist of his head, soon gave me to know I had nothing to dread. He spoke not a word, but went straight to his work. And filled all the stockings; then turned with a jerk

He spoke not a word, but went straight to his work. And filled all the stockings; then turned with a jerk And laying his finger aside of his nose. And giving a nod, up the chimney he rose.

And laying his finger aside of his nose. And giving a nod, up the chimney he rose. He sprang to his sleigh, to his team gave a whistle, and away they all flew like the down of a thistle. But I heard him exclaim 'ere he drove out of sight,

He sprang to his sleigh, to his team gave a whistle, and away they all flew like the down of a thistle. But I heard him exclaim 'ere he drove out of sight, "Happy Christmas to all and to all a good night!"

"Happy Christmas to all and to all a good night!"