More notes on

Athenian Film Archaeology

The closing sequence of the 1961 film

Dream Neighborhood (Η συνοικία το όνειρο) is a powerful moment in Greek cinema (see here on

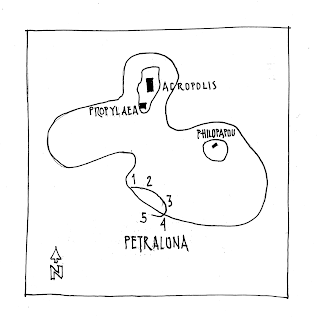

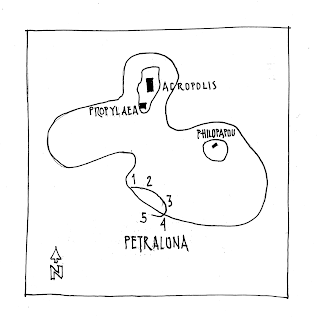

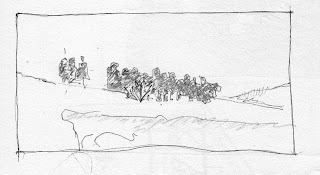

YouTube). A funerary procession leads the viewer from the hills of Ano Petralona to the shanty town neighborhood that forms the film's sociological subject. The film deserves an entire essay for its architectural narrative. This post hopes to unpack some of the basic spatial maneuvers. The sketch plan above shows the three major architectural subjects in Athenian topography. The camera is placed somewhere on the hill and tracks the funerary party as they process along the hill (offering views to the Acropolis and the Philopapous Monument) and then down into the impoverished architecture where the characters live. I've made five quick sketches to trace the movement along this sequence, numbered 1-5 above.

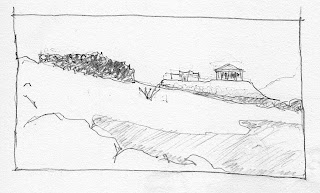

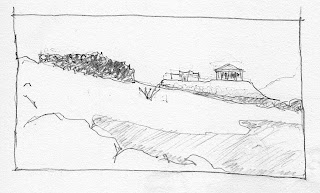

1. A black mass moves along the hill, counterbalancing the white architecture of the Parthenon and the Propylaea. The black mass is made up of the funerary party, a group of 20-30 individuals wearing black. The funerary party represents the pains of poverty and the negativity of self-destruction. Although the characters in the movie are not certain of this, the viewer knows that the dead man committed suicide, falling from the very same rocks. A bush at the middle ground of the frame creates a point of reference. A shaded triangular area in the foreground contains physical detail. The funerary part will eventually enter that foreground area and we will start discerning the actors' identities. The Acropolis serves as a silent icon in the distance. The mass to its left, the Propylaea are both the gateways to the ancient monument, but also the intermediary gate for the camera's movement. In a filmic conceit, the mourners will enter from the Propylaea to the Acropolis.

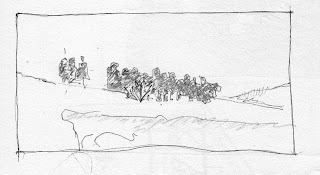

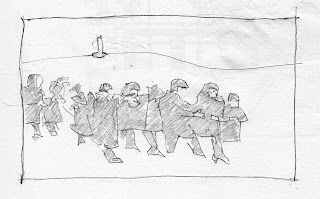

2. The black mass of mourners moves left to right while the camera zooms closer. The mourning poor have now come to the middle-ground of the bush. As they grow larger, they engulf the Acropolis and make it disappear. I read this as a visual statement of erasure. In the filmic environment blackness is more than the opposite of white, but the absence of projection. It becomes a hole in the screen. The audience is engulfed in the meaningless darkness of the movie theater (or the open air theater). Blackness within the projected frame is an interior duplication of the exterior darkness of the filmic existential drama.

3. The mourners continue to move left to right. The camera keeps them in the center of the frame by moving along with them. In the process, the Acropolis goes out of view and we focus to an area located northeast of the camera. The mourners have stopped riding on the landscape but are now engulfed by the limestone geology. We see the dead man's wife being supported by two elder females. Most importantly, we see the

Monument of Philopappos as an architectural signifier in the distance. Only those familiar with Athenian topography get the funerary subtext of this scene. The Philopappos monument is a first-century CE mausoleum of a Hellenistic prince from Syria. Although it seems as a mere column in the distance, the monument has a circular facade that reminds us of the circular movement of both the camera and the funerary party. The monument depicts Philopappos as riding through the city on a chariot and could be read as a filmic moment of its own right in stone. The Syrian origin of Philopappos might also trigger contemporary connotations, the fact that the impoverished subjects of the movie were Asia Minor refugees from 1922. The residents of Asyrmatou were refugees from Antalya.

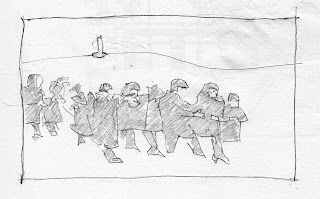

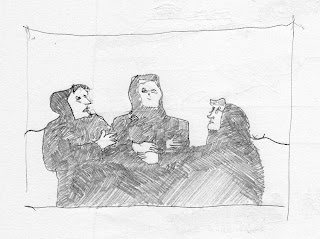

4. The camera has now focused on a triptych, the mourning widow physically propped up by two elder women. The widow stops over the precipice of the rock. She leans forward for a moment, suggesting that she would have flung herself from the hill if she were not supported by the mourners. This moment harks back to a similar shot where her husband alone committed suicide from the same spot. The religious references of this triad are pretty obvious.

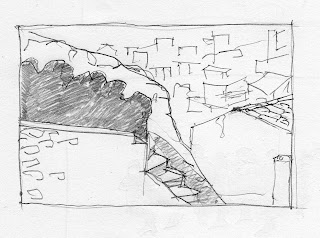

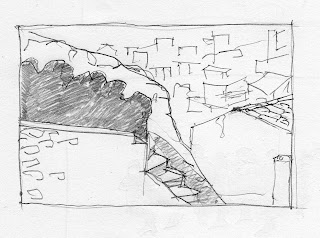

5. Having overcome sorrow and death, the mourners descend down the precipitous hill along a set of steps half natural half man-made. The camera now shows new Athens in all its modern poverty. The mourners have traveled the history of old glorious Athens and have annihilated in their descent to a different place below. I read the juxtaposition of great monuments and impoverished city as more than just a dialectic statement or an ironic juxtaposition between the unreal myth of Athens and the real hell of its existence. Rather, the mourners have eaten up the ancient topography and have, thus, overcome it. Antiquity is a point of reference in the distance far less interesting than the haphazard modern village. The subject of the film, Asyrmatou neighborhood, was located below the hills of Philopappos and above Troon Street. See

here for some views today.

The movie ends optimistically. Right as the mourners descend, a little boy ascends up the stairs with a kite, which he flies from the hill. The kite represents a resurrection. The final scene contains no ancient monuments. The architectural content of the resurrection is found within the kite itself which the camera stops to show in great detail. The kite is hand-drawn and shows a child's version of modern construction (subject to my next post)

Linda Nochlin: "Yes Richard Krautheimer. Can you imagine anything better? He'd break a desk every time pounding. I could do it for you, I could reenact for you his lecture on the building of Saint Peters in Rome. It was one of the most thrilling lectures. We started like pilgrims. He did it as pilgrims would see it. You know crossing the bridge, the Gianicolo, then the street, the narrow winding streets. And these pilgrims had come a long long way. Narrow little streets cluttered with ancient buildings and poverty stricken dwellings and so on. And then suddenly you came to the end of it and the whole piazza suddenly opened out. That huge light filled space, and all of Saint Peters was before you. I mean it was like a vision. It was just fabulous. And then you know, you went in, and it was sensational. And he told us that Mussolini had torn down all those ancient obstructions on the spina which made it so dark and then made the opening so magical. And we all hated Mussolini."

Linda Nochlin: "Yes Richard Krautheimer. Can you imagine anything better? He'd break a desk every time pounding. I could do it for you, I could reenact for you his lecture on the building of Saint Peters in Rome. It was one of the most thrilling lectures. We started like pilgrims. He did it as pilgrims would see it. You know crossing the bridge, the Gianicolo, then the street, the narrow winding streets. And these pilgrims had come a long long way. Narrow little streets cluttered with ancient buildings and poverty stricken dwellings and so on. And then suddenly you came to the end of it and the whole piazza suddenly opened out. That huge light filled space, and all of Saint Peters was before you. I mean it was like a vision. It was just fabulous. And then you know, you went in, and it was sensational. And he told us that Mussolini had torn down all those ancient obstructions on the spina which made it so dark and then made the opening so magical. And we all hated Mussolini."